Средноанглиски јазик

Средноанглискиот јазик (на англиски се означува со кратенката ME[1]) — облик на англискиот јазик што се зборувал по Норманските освојувања (1066 г.) на Велика Британија сѐ до крајот на XV век. Англискиот јазик претрпува особени промени и го доживува својот вистински развој по завршување на староанглискиот период. Во академскиот свет постојат различни мислења за периодот кога тој се говорел, но Оксвордскиот речник на англискиот јазик одредува дека средноанглискиот јазик се зборувал од 1150 до 1500 г.[2] Овој период на развој на англискиот јазик безмалку се поклопува со периодот на средниот и доцниот среден век.

| Средноанглиски јазик (Middle English) | |

|---|---|

| Englisch, Inglis, English | |

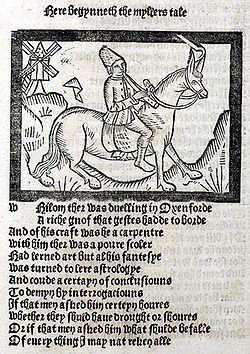

Една страна од Кантербериски приказни од Џефри Чосер | |

| Застапен во | Англија, делови од Велс, југоисточна Шкотска и шкотски населби, делумно и во Ирска |

| Ера | се развива во Раносовремен англиски јазик, Скотс, и Јола и Фингласки во Ирска до XVI век |

| Јазично семејство | индоевропски

|

| Претходни облици: | |

| Јазични кодови | |

| ISO 639-2 | enm |

| ISO 639-3 | enm |

| ISO 639-6 | meng |

|

| |

Околу 1470 г. со помош на пронајдокот на печатницата од страна на Јоханес Гутенберг во 1439 г., се воспоставила јазичната норма заснована на лондонскиот дијалект (Чансери). Овој стандардизиран јазик во голема мера ги воспоставува нормите за начинот на пишување на современиот англиски јазик, иако изговорот на зборовите со текот на времето значително ќе се измени. Средноанглискиот јазик ќе го замени ерата на раниот современ англиски јазик која трае до 1650 г. Скотс или Шкотскиот англиски јазик се развива во истиов период, но како варијанта на дијалектите од Нортамбрија (што најмногу се зборувале во северна Англија и југоисточна Шкотска).

Во текот на средноанглискиот период многу од староанглиските граматички особини или ќе станат поедноставни или пак севкупно ќе исчезнат. Инфлексиите кај именките, придавките и глаголите стануваат сѐ поедноставни прво преку нивно скратување (и на крајот целосно елиминирање) на граматичките падежи. Средноанглискиот јазик исто така во себе вклопува значителен број заемки од вокабуларот на Норманскиот француски јазик, особено на полето на политиката, правото, уметноста и религијата. Обичниот англиски вокабулар во најголема мера ја задржува германската етиологија, при што сѐ позабележителни стануваат влијанијата од Старонорвешкиот јазик. Се случуваат големи промени во изговорот, особено при изговарање на долгите вокали и дифтонзите, коишто во подоцнежниот средноанглиски период ќе го претрпат феноменот на скратување на долгите вокали (Great Vowel Shift).

Постојат само мал број сочувани дела од времето на средноанглиската книжевност, делумно поради норманската доминација и престижот што потекнувал од пишување на француски наспроти на англиски јазик. Во текот на XIV век се јавува нов стил на книжевност преку делата на писателите Џон Виклиф и Џефри Чосер, чии Кантербериски приказни се дело коешто е најпроучувано и најчитано од овој период.[4]

Примери

уредиПовеќето од преводите од средноанглиски на модерен англиски јазик што следуваат се препеви и не се буквални преводи.

Ormulum, XII век

уредиСтрофата ни дава увертира на Христовото рождество(3494–501):[5]

| Forrþrihht anan se time comm þatt ure Drihhtin wollde ben borenn i þiss middellærd forr all mannkinne nede he chæs himm sone kinnessmenn all swillke summ he wollde and whær he wollde borenn ben he chæs all att hiss wille. |

As soon as the time came that our Lord wanted be born in this middle-earth for all mankind sake, at once He chose kinsmen for Himself, all just as he wanted, and He decided that He would be born exactly where He wished. |

Епитафот на John the smyth, починал 1371 г.

уредиЕпитаф најден во епископската црква во Оксфордшир:[6][7]

| Изворен текст | Превод на Patricia Utechin[7] |

|---|---|

| man com & se how schal alle dede li: wen þow comes bad & bare noth hab ven ve awaẏ fare: All ẏs wermēs þt ve for care:— bot þt ve do for godẏs luf ve haue nothyng yare: hundyr þis graue lẏs John þe smẏth god yif his soule heuen grit |

Man, come and see how all dead men shall lie: when that comes bad and bare, we have nothing when we away fare: all that we care for is worms:— except for that which we do for God's sake, we have nothing ready: under this grave lies John the smith, God give his soul heavenly peace |

Библијата на Виклиф, 1384 г.

уредиОд Wycliffe's Bible, (1384):

| Прва верзија | Втора верзија | Превод |

|---|---|---|

| 1And it was don aftirward, and Jhesu made iorney by citees and castelis, prechinge and euangelysinge þe rewme of God, 2and twelue wiþ him; and summe wymmen þat weren heelid of wickide spiritis and syknessis, Marie, þat is clepid Mawdeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis wenten 3 out, and Jone, þe wyf of Chuse, procuratour of Eroude, and Susanne, and manye oþere, whiche mynystriden to him of her riches. | 1And it was don aftirward, and Jhesus made iourney bi citees and castels, prechynge and euangelisynge þe rewme of 2God, and twelue wiþ hym; and sum wymmen þat weren heelid of wickid spiritis and sijknessis, Marie, þat is clepid Maudeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis 3wenten out, and Joone, þe wijf of Chuse, þe procuratoure of Eroude, and Susanne, and many oþir, þat mynystriden to hym of her ritchesse. | 1And it came to pass afterward, that Jesus went throughout every city and village (castle), preaching and showing the kingdom of 2God, and the twelve were with him; and certain women, which had been healed of wicked spirits and sicknesses, Mary called Magdalene, out of whom 3went seven devils, and Joanna the wife of Chuza, the steward of Herod, and Susanna, and many others, which provided for Him from their substance. |

Чосер, околу 1390 г.

уредиСледи почетокот на главниот предговор на Кантербериските приказни од Џефри Чосер. Текстот е напишан на дијалект близок на лондонскиот, а запишувањето на зборовите личи на „Чансери стандардот“ за пишување на англискиот јазик што веќе во тоа време бил во употреба.

| Изворен текст на средноанглиски | Буквален превод на современ англиски[8] |

|---|---|

| Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote | When [that] April with his showers sweet |

| The droȝte of March hath perced to the roote | The drought of March has pierced to the root |

| And bathed every veyne in swich licour, | And bathed every vein in such liquor, |

| Of which vertu engendred is the flour; | Of which virtue engendered is the flower; |

| Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth | When Zephyrus eke with his sweet breath |

| Inspired hath in every holt and heeth | Inspired has in every holt and heath, |

| The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne | The tender crops; and the young sun |

| Hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne, | Has in the Ram his half-course run, |

| And smale foweles maken melodye, | And small fowls make melody, |

| That slepen al the nyght with open ye | That sleep all the night with open eye |

| (So priketh hem Nature in hir corages); | (So pricks them Nature in their courages); |

| Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages | Then folk long to go on pilgrimages |

| And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes | And palmers [for] to seek strange strands |

| To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; | To far-off hallows, couth in sundry lands; |

| And specially from every shires ende | And, especially, from every shire's end |

| Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, | Of England, to Canterbury they wend, |

| The hooly blisful martir for to seke | The holy blissful martyr [for] to seek, |

| That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke. | That them has helped, when [that] they were sick. |

Превод од средноанглиски во современа англиска проза: When April with its sweet showers has pierced March's drought to the root, bathing every vein in such liquid by whose virtue the flower is engendered, and when Zephyrus with his sweet breath has also enlivened the tender plants in every wood and field, and the early-year sun is halfway through Aries, and small birds that sleep all night with an open eye make melodies (their hearts so pricked by Nature), then people long to go on pilgrimages, and palmers seek foreign shores and distant shrines known in sundry lands, and especially they wend their way to Canterbury from every shire of England in order to seek the holy blessed martyr, who has helped them when they were ill.[9]

Гауер, 1390 г.

уредиСледи почетокот од прологот на делото Confessio Amantis од John Gower.

| Изворен средноанглиски текст | Буквален превод на современ англиски: | Препев современ англиски: (Richard Brodie)[10] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Превод во модерна англиска проза:

The books of those that wrote before us survive, and therefore we are taught about what was written then. For this reason it is good that we also in our time, here among us, write some material from scratch, inspired by the example of these old customs; so that it might, when we are dead and elsewhere, be left to the world's ear in the time coming after this. But because men say, and it's true, that when someone writes entirely about wisdom, it often dulls a man's wit who reads it every day. For that reason, if you permit it, I would like to take the middle way, and write a book between the two, somewhat of passion, somewhat of instruction, that whether of high or low status, people may like what I write about.

Поврзано

уреди- Medulla Grammatice (колекција на вокабулари)

- Middle English creole hypothesis

- Средноанглиски речник

- Средноанглиска книжевност

Литература и наводи

уреди- ↑ Simon Horobin, Introduction to Middle English, Edinburgh 2016, s. 1.1.

- ↑ „Middle English–an overview - Oxford English Dictionary“. Oxford English Dictionary (англиски). 2012-08-16. Архивирано од изворникот на 2012-09-17. Посетено на 2016-01-04.

- ↑ Carlson, David. (2004). „The Chronology of Lydgate's Chaucer References“. The Chaucer Review. 38 (3): 246–254. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.7778. doi:10.1353/cr.2004.0003.

- ↑ The name "tales of Canterbury" appears within the surviving texts of Chaucer's work.[3]

- ↑ Holt, Robert, уред. (1878). The Ormulum: with the notes and glossary of Dr R. M. White. Two vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Internet Archive: Volume 1; Volume 2.

- ↑ Bertram, Jerome (2003). „Medieval Inscriptions in Oxfordshire“ (PDF). Oxoniensia. LXVVIII: 30. ISSN 0308-5562.

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 Utechin, Patricia (1990) [1980]. Epitaphs from Oxfordshire (2. изд.). Oxford: Robert Dugdale. стр. 39. ISBN 978-0-946976-04-1.

- ↑ This Wikipedia translation closely mirrors the translation found here: Canterbury Tales (selected) (revised. изд.). Barron's Educational Series. 1970. стр. 2. ISBN 9780812000399.

when april, with his.

- ↑ Sweet, Henry (d. 1912) (2005). First Middle English Primer. Evolution Publishing: Bristol, Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-1-889758-70-1.

- ↑ Brodie, Richard (2005). „John Gower's 'Confessio Amantis' Modern English Version“. "Prologue". Архивирано од изворникот на 2013-03-29. Посетено на March 15, 2012.

- Brunner, Karl (1962) Abriss der mittelenglischen Grammatik; 5. Auflage. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer (1st ed. Halle (Saale): M. Niemeyer, 1938)

- Brunner, Karl (1963) An Outline of Middle English Grammar; translated by Grahame Johnston. Oxford: Blackwell

- Mustanoja, Tauno (1960) "A Middle English Syntax. 1. Parts of Speech". Helsinki : Société néophilologique.

Надворешни врски

уреди| Wikisource has several original texts related to: Middle English works |

| Викимедииниот Инкубатор испробува Википедија на средноанглиски јазик |

- A. L. Mayhew and Walter William Skeat. A Concise Dictionary of Middle English from A.D. 1150 to 1580

- Middle English Glossary

- Oliver Farrar Emerson, уред. (1915). A Middle English Reader. Macmillan. With grammatical introduction, notes, and glossary.