Прв алија

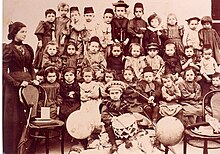

Првиот алија (хебрејски: העלייה הראשונה, HaAliyah HaRishona) или познат и како земјоделски алија, бил првиот голем бран на ционистичко доселување (алија) во отоманска Палестина помеѓу 1881 и 1903 година. .[1][2] Евреите кои мигрирале за време на овој бран потекнувале претежно од источна Европа и од Јемен. Околу 25 [3] –35 000[4] Евреи се доселиле за време на овој бран. Голем дел од европските еврејски имигранти во периодот од крајот на 19 и почетокот на 20-от век се откажале по неколку месеци и се вратиле во нивните земји, честопати страдајќи од глад и болести.[5] Бидејќи имало имиграција во Палестина и во претходните години, употребата на терминот „Прва Алија“ е контроверзна.[6]

Скоро сите Евреи од Источна Европа пред тоа време потекнувале од традиционални еврејски семејства. Имигрантите кои биле дел од Првиот Алија излегле повеќе од врска со земјата на нивните предци.[3][7] Повеќето од овие имигранти работеле како занаетчии или во мала трговија, но многумина работеле и со земјоделство. Само некои од нив дошле организирано, со помош на Ховевеј Цион, но повеќето биле неорганизирани.

Првиот Алија се сметал за успешен низ очите на некои историчари, бидејќи ционистите биле во можност да мигрираат и да напредуваат економски во Палестина. Само мало малцинство од 6.000 кои емигрирале, околу 2%, останале во Османлиска Палестина. Според „Еврејската виртуелна библиотека“ скоро пола од делениците за време на Првиот Алија не останале во Палестина/ Израел.[8]

Источноевропски Евреи

уредиЕврејската имиграција во Османлиска Палестина од Источна Европа се создала како дел од масовните емиграции на приближно 2,5 милиони луѓе[9], емиграција која се одвивала кон крајот на 19 и почетокот на 20 век. Брзиот пораст на населението создал економски проблеми што ги засегнале еврејските општества во Русија, Галиција и Романија.

Прогонството на Евреите во Русија исто така било фактор. Во 1881 година бил убиен царот Александар Втори од Русија, а властите ги обвиниле Евреите за атентатот. Следствено, покрај законите во мај, големите антиеврејски погроми ја зафатиле евреиските населби. Движење наречено Ховевеј Цион (љубов кон Цион) се раширил низ еврејските населби. Двете движења ги охрабриле Евреите да емигрираат во Османлиска Палестина.

Јемен

уредиПрвата група на јеменски Евреи дошле околу 7 месеци пред да дојдат источноевропските Евреи во Палестина.

Населби

уредиПрвиот алија ги поставил темелите на еврејските наслеби во Израел. Населби кои биле основани од деселеници за време на Првиот Алија се:

- Ришон Лецион (1882)

- Рош Пина (1882)

- Цихрон Јаков (1882)

- Петах Тиква (1882)

- Мазкерет Батја (1883)

- Нес Циона (1883)

- Јесуд Намала (1883)

- Гедера (1884)

- Бат Шломо (1889)

- Меир Шфеја (1889)

- Реховот (1890)

- Мишмар Хајарден (1890)

- Хадера (1891)

- Ејн Зејтим (1892)

- Моца (1894)

- Хартув (1895)

- Метула (1896)

- Бер Тувија (1896)

- Бнеј Јехуда (1898)

- Маханајим (1898–1912)

- Иланија (1899)

- Меша (1901), преименувано во Кфар Тавор in 1903

- Јавнел (1901)

- Менахемија (1901)

- Бејт Ган (1903)

- Атлит (1903)

- Бинјамина-Гиват Ада (1903)

- Кфар Саба (1904)

Белешки

уреди- ↑ Bernstein, Deborah S. Pioneers and Homemakers: Jewish Women in Pre-State IsraelState University of New York Press, Albany. (1992) p.4

- ↑ Scharfstein, Sol, Chronicle of Jewish History: From the Patriarchs to the 21st Century, p.231, KTAV Publishing House (1997), ISBN 0-88125-545-9

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 „New Aliyah - Modern Zionist Aliyot (1882 - 1948)“. Jewish Agency for Israel. Архивирано од изворникот на 2009-06-23. Посетено на 2008-10-26.

- ↑ „The First Aliyah (1882-1903)“. www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Посетено на 13 February 2020.

- ↑ Joel Brinkley, As Jerusalem Labors to Settle Soviet Jews, Native Israelis Slip Quietly Away, The New York Times, 11 February 1990. Quote: "In the late 19th and early 20th century many of the European Jews who set up religious settlements in Palestine gave up after a few months and returned home, often hungry and diseased.". Accessed 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Halpern, Ben (1998). Zionism and the creation of a new society. Reinharz, Jehuda. New York: Oxford University Press. стр. 53–54. ISBN 0-585-18273-6. OCLC 44960036.

It is the accepted convention to divide the flow of Jewish immigrants into a series of aliyot (sing., aliyah), or waves of newcomers, each of which made a characteristic contribution to the New Yishuv's developing institutional structure. The final product, the base upon which Israel was founded, is pictured as a stratified deposit of the historic achievements of the successive aliyot from 1881 to 1948. Like most historical generalizations, these too are useful mainly as points of departure. The actual course of events does not follow closely the lines they lay down, but the profile of history is illuminated when one plots the curve of deviations from these initial assumptions. The First Aliyah, from 1881 to 1903, is said to have brought those pioneers who first established Jewish plantation colonies, the moshavot (sing., moshavah), the mainstay of Israel's private agricultural sector. This observation merely provides a skeletal (and incomplete) framework rather than a full description of Israel's institutional development during that period. From 1881 to 1903, Palestine Jewry is estimated to have increased from about 22,000 or 24,000 to about 47,000 or 50,000, mainly because of immigration in 1881-84 and 1890-91. Of the 20,000 to 30,000 newcomers, only 3,000 settled in the new moshavot, the characteristic achievement of the First Aliyah. On the other hand, Jerusalem, the stronghold of the established institutions of the Old Yishuv, increased from 14,000 to 28,000, by far the greater part of whom were undoubtedly absorbed into the traditionalist community. Thus, considered in the light of demographic statistics, Jewish immigration to Palestine from 1881 to 1914 was largely a continuation of its pre-Zionist past. The specific historic importance of Zionism in the population transfer is nevertheless said to have been that a number of Jewish plantation villages and the beginnings of a farmer-worker class were established. This conclusion, too, has been contested. The polemical bias of the criticism is sometimes transparent, but it has underscored significant qualifications nevertheless. Characteristically Zionist innovations such as the revival of spoken Hebrew were "foreshadowed" by "precursors" in earlier generations. Opposition to the revival of spoken Hebrew became a hallmark of the Ashkenazi traditionalist establishment only after Zionism arose. In earlier decades, many had defended the holy tongue in Europe as one of the main points in their resistance to religious modernism; in Palestine, there were traditionalists who practiced Hebrew speaking as a religious exercise, and even dreamed of its revival as the national vernacular. Moreover, the rigid ideological separation of the two camps after Zionism arose was neither immediate nor complete; some settlers belonged to both the old and the new social structures.

CS1-одржување: датум и година (link) - ↑ Palestine/Israel

- ↑ The First Aliyah (1882-1903) Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ „Industrial Revolution“. www.let.leidenuniv.nl. Архивирано од изворникот на 2018-04-05. Посетено на 13 February 2020.

Литература

уреди- Kark, Ruth; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs. Magnes Press. ISBN 0-8143-2909-8.

- Ben-Gurion, David (1976), From Class to Nation: Reflections on the Vocation and Mission of the Labor Movement, Am Oved (хебрејски)